Author: Jadranka Bokan

Only when an adjective is placed BEFORE A NOUN (thus, on its LEFT side) it gets some endings.

Otherwise (when it is a part of the predicate i.e. when it is placed on the RIGHT side of the noun) it remains in its basic form:

die schöne Frau ist Model. <-> Die Frau ist schön/.

We are going to take a closer look to the case when the adjective stands before a noun and the logic behind the endings that it gets.

Let’s make one thing clear:

Adjective builds one logical and grammatical unit with the word that stands before it and the noun that stands behind it and it cannot be considered outside of that unit.

Before the adjective can be placed either:

1.) nothing (Null article) or

2.) the definite article or

3.) indefinite article

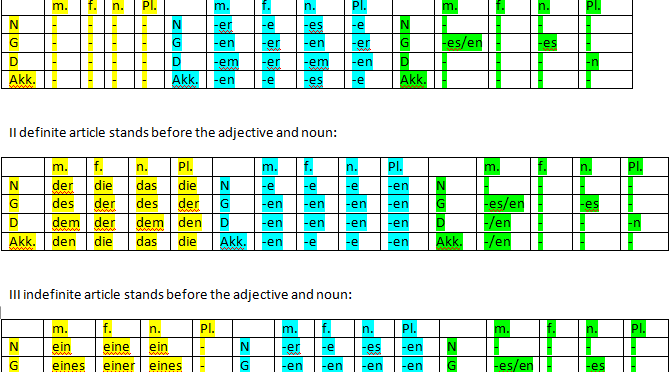

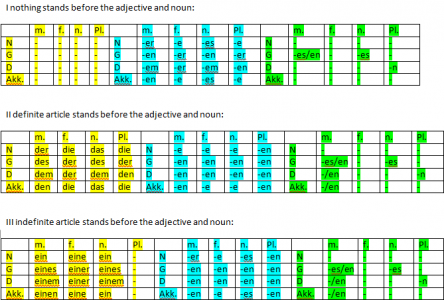

This is how it looks like:

Ø / definite article / indefinite article + adjective + noun

Since articles vary in their“informative” value, the endings of the adjective will also differ in accordance with that.

Let me explain what this means:

If there is no word before the adjective, that means that the ending of the adjective will HAVE TO be VERY informative and provide all the information on:

1) the number of the noun (singular/plural),

2) the gender of that noun (masculine, feminine or neuter) and

3) the case (Nominative / Genitive / Dative / Accusative).

In this case, the adjective gets the endings of the definite article and that is why we call this adjective declension “strong”.

On the other hand, when definite article stands before the adjective, since it is very informative, the endings of the adjective do not have to be very informative, and the adjective gets only –e or –en. This is why this declension is the so called “week” declension.

The so called “mixed” Adjective declension is a combination of the “strong” and the “week” one: it has “borrowed” the endings for the Nominative and Accusative from the strong one and -en endings from the “week” one.

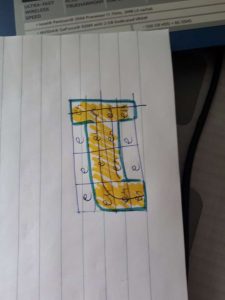

If you cannot remember the arrangement of the endings -en in the “week” and “mixed” declension, here is something that can help: if you turn around the table with these adjective endings you will be able to see that the -en endings form a small letter t:

Now when we have cleared everything out, it will be much easier to memorize the numerous endings in the declination of Adjectives. My recommendation is: always take into consideration the endings of the article when you learn the adjective endings, because the logic behind the whole story becomes much clearer that way.

This is how the endings of the adjective look like in a “sandwich” i.e after the word that stands before it (and the noun that stands behind it), where yellow are the endings of the article, blue are endings of the adjective and green are endings of the noun:

Other words that can appear instead of definite article: dieser, diese, dieses, diese; jeder, jede, jedes, alle; mancher, manche, manches, manche.

Other words that can appear instead of indefinite article: kein, keine, kein and possessiv pronouns (mein, dein, sein, ihr, unser, euer, ihr).

if you have read this post until the end, you deserved one extra tip: after “viele” the adjective gets the ending -e and after “alle” the adjective gets the ending -en:

viele neuE Autos, alle gutEN Kinder

Another respectful source of the theory about the adjective declension: Declension of adjectives in German Grammar